Last Updated on April 1, 2020

Blood transfusion is generally the process of infusing blood or blood products into one’s circulation intravenously. Globally around 85 million units of red blood cells are transfused in a given year.

Blood transfusion is indicated for replacing lost components of the blood.

Earlier whole blood was transfused but the modern practice is to transfuse only components of the blood, such as red blood cells, white blood cells, plasma, clotting factors, and platelets.

Indications of component transfusion vary.

For example, red blood cell transfusions are done for hemorrhage and to improve oxygen delivery to tissues [ symptomatic anemia, acute sickle cell crisis, and acute blood loss, etc].

For reversal of anticoagulants fresh frozen plasma is used.

Similarly, platelet transfusion is indicated to prevent hemorrhage in patients with thrombocytopenia or platelet function defects.

Cryoprecipitate is used in cases of hypofibrinogenemia, often in the setting of massive hemorrhage or consumptive coagulopathy.

Detailed blood transfusion indications have been discussed below.

Indications for Transfusion of Blood and Blood Products

Red Blood Cells

Packed red blood cells are prepared from whole blood by removing the plasma.

One unit transfusion increases levels of hemoglobin by 1 g per dL and hematocrit by 3%.

RBC transfusions are used to treat hemorrhage and to improve oxygen delivery to tissues.

Indications for RBC transfusion include

- Acute sickle cell crisis [for prevention of stroke]

- Acute blood loss > 30% of blood volume.

- Patients with symptomatic anemia

- Hemoglobin < 7 g per dL

Plasma

Plasma contains all of the coagulation factors.

Indications for transfusion of plasma products

- Patients on anticoagulant therapy with international normalized ratio > 1.6

- Prevent active bleeding in a patient on anticoagulant therapy before a procedure

- Active bleeding

- Emergent reversal of warfarin

- Major or intracranial hemorrhage

- Prophylactic transfusion in a surgical procedure that cannot be delayed

- Acute disseminated intravascular coagulopathy

- Microvascular bleeding during massive transfusion

Platelets

Platelet transfusion may be indicated to prevent hemorrhage in patients with thrombocytopenia or platelet function defects.

One unit of apheresis platelets should increase the platelet count in adults by 30×103 per μL.

Spontaneous bleeding through intact endothelium does not occur unless the platelet count is no greater than 5 × 103 per μL.

Indications for Transfusion of Platelets in Adults [Platelet count where transfusion should be given is indicated in brackets]

- Major surgery or invasive procedure, no active bleeding [≤ 50 × 103 per μL]

- Ocular surgery or neurosurgery, no active bleeding [≤ 100 x 103 per μL]

- Surgery with active bleeding

- < 50 x 103 per μL (usually)

- > 100 x 103 per μL (rarely)

- Stable, nonbleeding < 10 x 103 per μL

- Stable, nonbleeding, and body temperature > 100.4°F or undergoing invasive procedure < 20 x 103 per μL

Indications for Transfusion of Platelets in Neonates

| Platelet count (× 103 per μL) | Indications |

| < 20 | Always transfuse |

| 20 to < 30 | Consider transfusion; transfuse for clinical reasons (e.g., active bleeding, lumbar puncture) |

| 30 to 50 | Transfuse if any of the following indications exist: |

| · First week of life with birth weight < 1,000 g (2 lb, 4 oz) | |

| · Intraventricular or intraparenchymal cerebral hemorrhage | |

| · Coagulation disorder | |

| · Sepsis or fluctuating arterial-venous pressures | |

| · Invasive procedure | |

| · Alloimmune neonatal thrombocytopenia* |

Contraindications to platelet transfusion are

- Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura

- Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia.

Transfusion of platelets in these conditions can result in further thrombosis.

Cryoprecipitate

Cryoprecipitate contains high concentrations of factor VIII and fibrinogen. Cryoprecipitate is used in cases of hypofibrinogenemia, which most often occurs in the setting of massive hemorrhage or consumptive coagulopathy.

Indications for Transfusion of Cryoprecipitate

Adults

- Hemorrhage after cardiac surgery

- Massive hemorrhage or transfusion

- Surgical bleeding

Neonates

- Anticoagulant factor VIII deficiency

- Anticoagulant factor XIII deficiency

- Congenital dysfibrinogenemia

- Congenital fibrinogen deficiency

- von Willebrand disease

Procedure of Blood Collection and Storage

Blood transfusion that uses someone else’s blood is called allogeneic or homologous transfusion. There is also an increasing trend of using one’s own blood or autologous transfusion.

However, homologous transfusion is more common than autologous blood transfusion.

Blood is most commonly donated as whole blood intravenously and collected with an anticoagulant.

After donation, the blood follows cycle of testing for various pathogens, separation into components, storage, and administration to the recipient.

All donated blood should be tested for transfusion transmissible infections.

These include HIV, Hepatitis B, Hepatitis C and Treponema pallidum (syphilis). Depending on the endemicity of the disease and regulations of specific countries more pathogens can be added to the list.

All donated blood should also be tested for the ABO blood group system and Rh blood group system to ensure that the patient is receiving compatible blood.

Before transfusing, the donor and recipient’s samples are cross-matched to ensure compatibility.

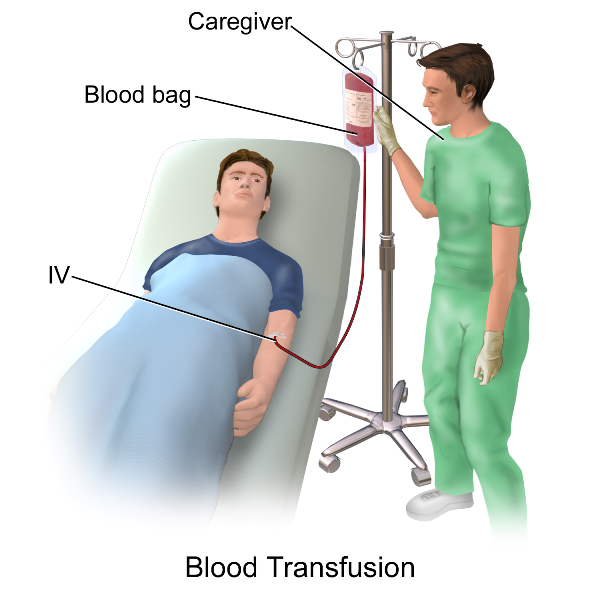

Procedure of Blood Transfusion

Like most medical procedures, a blood transfusion will take place in a hospital or clinic.

The patient’s blood pressure, pulse, and temperature are noted before starting the transfusion.

The blood transfusion procedure begins when an intravenous (IV) line is placed onto the patient’s body. It is through the IV that the patient will begin to receive the new blood. Depending on the amount of blood, a simple blood transfusion can take between 1-4 hours.

The patient is monitored for vitals and any other sign of transfusion reaction.

Following the completion of the blood transfusion, the patient’s vital signs are checked and the IV is removed.

Complications of Blood Transfusion

Transfusion-related complications can be categorized as acute or delayed. These can be further classified as infectious and non-infectious.

Acute complications occur within minutes to 24 hours of the transfusion, whereas delayed complications may develop days, months, or even years later.

Transfusion-related infections are less common because of advances in the blood screening process.

Therefore, patients are far more likely to experience non-infectious complications [also termed non-infectious serious hazard of transfusion] than an infectious complication.

Non-infectious Serious Hazards of Transfusion

Acute

- Acute hemolytic reaction

- Allergic reaction

- Anaphylactic reaction

- Coagulation problems in massive transfusion

- Febrile nonhemolytic reaction

- Metabolic derangements

- Mistransfusion (transfusion of the incorrect product to the incorrect recipient)

- Septic or bacterial contamination

- Transfusion-associated circulatory overload

- Transfusion-related acute lung injury

- Urticarial reaction

Delayed

- Delayed hemolytic reaction

- Iron overload

- Over transfusion or under transfusion

- Post-transfusion purpura

- Transfusion-associated graft-versus-host disease

- Transfusion-related immunomodulation

Infectious Complications of Blood Transfusions

| Complication | Estimated risk |

| Hepatitis B virus | 1 in 350,000 |

| Hepatitis C virus | 1 in 1.8 million |

| Human T-lymphotropic virus 1 or 2 | 1 in 2 million |

| Human immunodeficiency virus | 1 in 2.3 million |

| Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease | Rare |

| Human herpesvirus 8 | Rare |

| Malaria and babesiosis | Rare |

| Pandemic influenza | Rare |

| West Nile virus | Rare |

Acute Transfusion Reactions

Acute Hemolytic Reactions

The incidence of acute hemolytic reactions is approximately one to five per 50,000 transfusions.

Hemolytic transfusion reactions can be caused by immune destruction of transfused RBCs, by the recipient’s antibodies.

Nonimmune causes of acute reactions are

- Bacterial overgrowth

- Improper storing

- Infusion with incompatible medications

- Infusion of blood through lines containing hypotonic solutions

- Small-bore intravenous tubes.

There are two categories of hemolytic transfusion reactions: acute and delayed.

In acute hemolytic transfusion reactions, there is a destruction of the donor’s RBCs within 24 hours of transfusion. The most common type is extravascular hemolysis due to antibodies against donor RBCs.

Intravascular hemolysis is a severe form of hemolysis caused by ABO antibodies.

Symptoms of acute hemolytic transfusion reactions are

- Fever with chills and rigors

- Nausea and vomiting

- Dyspnea

- Hypotension

- Diffuse bleeding

- Hemoglobinuria

- Decreased urine output [oliguria, anuria]

- Pain at the infusion site

- Chest, back, and abdominal pain.

Associated complications

- Significant anemia

- Acute renal failure

- Disseminated intravascular coagulation

- Death

Allergic Reactions

Allergic reactions range from mild (urticaria) to life-threatening (anaphylactic shock)

Avoiding plasma transfusions with IgA in patients known to be IgA deficient may help.

Cellular products (e.g., RBCs, platelets) may be washed to remove plasma in patients with an IgA deficiency.

The patient must be strictly observed during the initial 15 minutes of transfusion.

Transfusion Related Acute Lung Injury

Transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI) is noncardiogenic pulmonary edema causing acute hypoxemia that occurs within six hours of a transfusion.

Read more about transfusion-related acute lung injury here

Febrile Nonhemolytic Transfusion Reactions

This is characterized by a rise in body temperature of at least 1°C within 24 hours after a transfusion. It may involve rigors, chills, and discomfort. The fever occurs more often in patients who have been transfused repeatedly and in patients who have been pregnant.

Leukoreduction, which is the removal or filtration of white blood cells from donor blood, has decreased febrile nonhemolytic transfusion reaction rates.

Febrile nonhemolytic transfusion reactions are caused by platelet transfusions more often than RBC transfusions due to the release of antibody-mediated endogenous pyrogen, and a release of cytokines.

Transfusion-Associated Circulatory Overload

Transfusion-associated circulatory overload is the result of a rapid transfusion of a blood volume that is more than what the recipient’s circulatory system can handle.

Patients with underlying cardiopulmonary compromise, renal failure, or chronic anemia, and infants or older patients are at the highest risk.

Clinical Features

- Tachycardia

- Cough

- Dyspnea

- Hypertension

- Elevated central venous pressure,

- Elevated pulmonary wedge pressure

- Widened pulse pressure

- Cardiomegaly

- Pulmonary edema

- Elevated brain natriuretic peptide levels

Delayed Transfusion Reactions

Transfusion-Associated Graft-Versus-Host Disease

Transfusion-associated graft-versus-host disease is a result of a donor’s lymphocytes proliferating and causing an immune attack against the recipient’s tissues and organs.

It is fatal in more than 90 percent of cases.

Immunocompromised or immunocompetent patients who are receiving transfusion with shared HLA haplotypes.

Symptoms include rash, fever, diarrhea, liver dysfunction, and pancytopenia that occurs one to six weeks after transfusion.