Last Updated on March 12, 2021

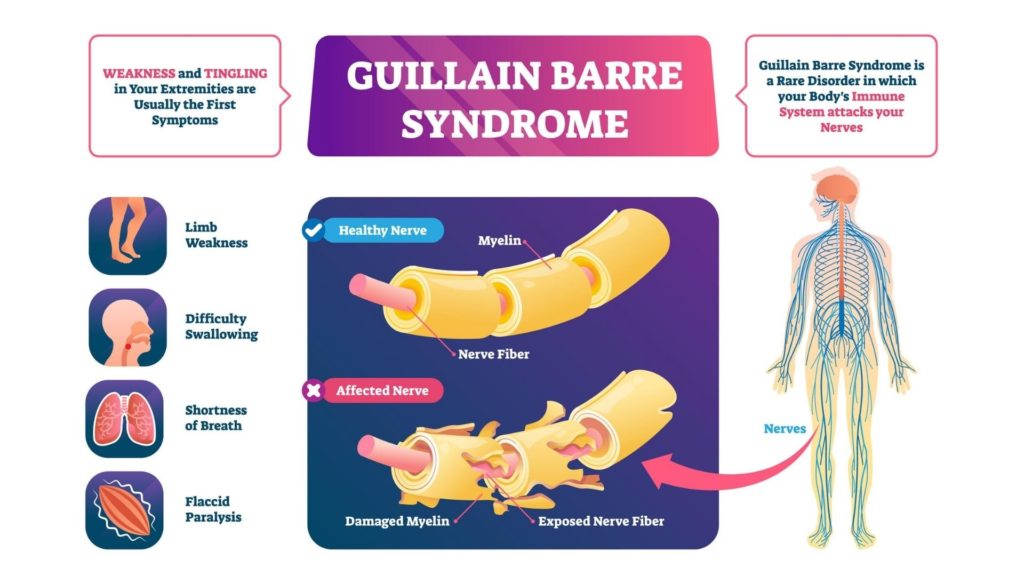

Guillain Barre syndrome (GBS) is a rare neurological disorder in which the body’s immune system attacks the peripheral nerves.

Peripheral nerves are a network of nerves present in the peripheral nervous system. The peripheral nervous system refers to parts of the nervous system outside the brain and spinal cord. It includes the cranial nerves, spinal nerves along with their roots and branches, peripheral nerves, and neuromuscular junctions.

It can affect people of all ages including children. However, it is more common in adults and in males.

GBS can range from a mild disease showing only brief weakness to severe form showing near-total paralysis. Severe cases may even make the person unable to breathe independently.

Fortunately, most people recover fully from even the most severe form of GBS.

After recovery, some people continue to have some degree of weakness.

Guillain-Barre syndrome is a potentially life-threatening disease. Patients need to be properly treated and monitored. Some patients may require intensive care. Treatment includes immunological therapies, emotional support, and rehabilitation.

The distribution of different subtypes of GBS varies between countries. In Europe and the United States, the majority of people have the demyelinating subtype (AIDP), and AMAN affects only a small number. In Asia and Central and South America, the majority of people are affected by AMAN. Miller Fisher variant is more commonly seen in Southeast Asia. These differences may be due to exposure to different kinds of infection as well as the difference in genetic susceptibility of various populations.

Causes of Guillain-Barre Syndrome

The exact cause of the disease is not known.

It is neither contagious nor an inherited disease.

Most cases usually begin a few days or weeks following a respiratory or gastrointestinal bacterial or viral infection. Infection with the Zika virus has been implicated in many cases of GBS. Guillain-Barre syndrome may also occur after Covid-19 infection. In rare cases, surgery or vaccinations may trigger the disease.

GBS is thought to be an autoimmune disease in which the person’s immune system begins to attack the body itself.

The immune attack that is initiated by the body to fight an infection mistakenly attacks the healthy nerves of the body. Since the body’s own immune system is responsible for causing the damage, GBS is called an autoimmune disease (“auto” meaning “self”).

Mechanism of Nerve Damage in GBS

The nerve dysfunction in GBS occurs due to an immune attack on the nerve cells of the peripheral nervous system.

The long projection of the nerve called the axons carries electrical nerve impulses to the neuromuscular junction, where the impulse is transferred to the muscle. Axons are covered by a sheath of Schwann cells that contain myelin. Nodes of Ranvier are the gaps between Schwann cells where the axon is exposed.

Different types of Guillain–Barré syndrome show different types of immune attack.

The demyelinating variant (AIDP) is characterized by damage to the myelin sheath by white blood cells.

The axonal variant is characterized by damage to the axons by IgG antibodies. These antibodies bind to gangliosides, which are a group of substances found in peripheral nerves.

The main four gangliosides against which antibodies have been described are GM1, GD1a, GT1a, and GQ1b. Different anti-ganglioside antibodies are associated with particular features; for instance, GQ1b antibodies have been linked with Miller Fisher variant of GBS.

Risk Factors

- Increasing age

- Bacterial infection with campylobacter

- Zika virus

- Influenza virus

- Cytomegalovirus

- Epstein-Barr virus

- Hepatitis A, B, C, and E

- HIV

- Mycoplasma pneumonia

- Covid-19 infection

- Surgery

- Influenza or other childhood vaccinations

- Trauma

Types of Guillain Barre Syndrome

Several subtypes of Guillain–Barré syndrome are recognized. However, many people have overlapping symptoms so that the classification becomes difficult in individual cases.

The most common types of GBS are as follows:

Acute inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy (AIDP):

- The weakness usually begins in the lower part of the body and slowly ascends to the other body parts.

- Most common in Europe and North America.

- There is no clear association with antiganglioside antibodies.

Miller Fisher syndrome (MFS)

- It is characterized by eye muscle weakness and ataxia. Usually, there is no limb weakness.

- It is more prevalent in Asia. In the US, it accounts for about 5-10% of cases of GBS.

- GQ1b, GT1a are the antiganglioside antibodies present in this condition.

Acute motor axonal neuropathy (AMAN)

- These are rare in the US but more common in Japan, China, and Mexico.

- It is characterized by isolated muscle weakness without sensory symptoms. Cranial nerve involvement is uncommon.

- GM1a/b, GD1a & GalNac-GD1a are the associated antiganglioside antibodies

Acute motor-sensory axonal neuropathy (AMSAN)

- AMSAN shows severe muscle weakness similar to AMAN but with sensory loss.

- GM1 and GD1a are the antiganglioside antibodies seen in this variant.

Pharyngeal-cervical-brachial variant

- It mainly shows weakness of the muscles of the throat, face, neck, and shoulder.

- Mostly GT1a, occasionally GQ1b, rarely GD1a

Signs and Symptoms

Unexplained sensations like tingling or weakness in the feet or hands, or pain starting in the legs or back may be the first sign of the disease.

Children may present with difficulty in walking or may refuse to walk.

Weakness on both sides of the body is the major symptom. It may present as difficulty climbing stairs or difficulty in walking.

The main signs and symptoms of Guillain-Barre syndrome include:

- Pricking or pins and needles sensations in the hands and feet

- Weakness in legs that later spreads to the upper body

- Severe pain that may be worse at night

- Unsteady walking or inability to walk or climb stairs

- Inability to move eyes, difficulty with vision, or double vision

- Difficulty swallowing, speaking, or chewing

- Difficulty with bladder control or bowel function

- Rapid heart rate

- Low or high blood pressure

- Difficulty breathing

These symptoms can increase in intensity over a period of time and may even progress to complete paralysis. When breathing, heart rate, or blood pressure get affected, the disease may become life-threatening.

Complications

- Breathing problems. Spread of weakness or paralysis to the muscles that control breathing can cause breathing difficulties. It can be a life-threatening complication. About one-fifth of patients with GBS require mechanical ventilation temporarily within the first week of hospitalization.

- Heart and blood pressure problems. Fluctuations in blood pressure and irregular heartbeats (cardiac arrhythmias) are common complications of Guillain-Barre syndrome.

- Bowel and bladder function problems. Sluggish bowel function and/or urinary retention may also occur.

- Pressure sores. Due to immobility and being bedridden, the patients are at an increased risk of developing bedsores or pressure sores.

- Blood clots. Immobility also increases the risk of developing blood clots.

- Residual numbness or other sensations. Most of the patients with Guillain-Barre syndrome recover fully. However, few experience minor, residual weakness, numbness, or tingling sensation.

- Pain. About one-third of patients experience severe nerve pain. This can be managed with proper medication.

- Relapse. About 2-5% of GBS patients experience a relapse.

- Death. In some cases, the disease may be fatal. This mainly occurs due to respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), cardiac arrest, or thromboembolism.

Diagnosis

A detailed medical history and a thorough physical examination are essential for the proper diagnosis of GBS.

The diagnosis of Guillain–Barré syndrome depends on the following clinical features:

- Involvement of both sides of the body.

- Rapid development of muscle weakness within a few days or weeks (in other neurological disorders, muscle weakness may take few months to progress).

- Absent reflexes. The deep tendon reflexes in the legs, such as knee jerks are usually lost. There may also be a loss of reflexes in the arms.

- Absence of fever.

In the early stages, it is difficult to diagnose the disease as the signs and symptoms are similar to other neurological disorders. Also, the initial features are different in different people.

Spinal tap (lumbar puncture)

Lumbar puncture for cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis may be carried out. In this procedure, a small amount of fluid (CSF) is withdrawn from the spinal canal in the lower back. This fluid is then examined in the laboratory.

GBS patients show an increase in CSF protein (>0.55 g/L) without an increase in white blood cells. The increase in CSF protein in GBS occurs due to the widespread inflammation of the nerve roots.

Read more about Lumbar Puncture or Spinal Tap-Indications, Procedure and Complications

Read more about Cerebro Spinal Fluid Analysis

Electromyography

Thin-needle electrodes are inserted into the muscles. These electrodes help to measure nerve activity in the muscles.

Nerve conduction studies

Electrodes are placed and taped on the skin above the nerves. A small shock is passed through the nerve to measure the speed of nerve signals.

In GBS, due to demyelination, the signals traveling along the nerve are slow. Hence, nerve conduction velocity test that measures the nerve’s ability to send a signal can help to diagnose GBS.

Serum autoantibodies

Measurement of serum autoantibodies is not routinely done in GBS but may be carried out if the diagnosis is doubtful.

Antibodies to gangliosides are found in about 60-70% of patients with GBS during the acute phase. GM1, GD1a, GT1a, and GQ1b are the specific antibodies found in association with different types of GBS.

Imaging studies

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) of the spine may be carried out to exclude other causes of limb weakness, such as spinal cord compression.

Evaluation of lung function

It should be carried out regularly to monitor respiratory status and the need for ventilatory support.

Blood tests

Routine blood tests such as complete blood count and serum electrolytes are carried out to rule out other neurological disorders having similar signs and symptoms.

Treatment

There is no known cure for GBS. In most cases, the disease is self-limiting, meaning it will resolve on its own. However, treatment can help to improve symptoms and shorten the duration of the disease.

As the disease may be life-threatening, the patients should be hospitalized so that they can be monitored closely.

Since GBS is an autoimmune disease, its acute phase is usually treated with intravenous immunoglobulin administration or by plasma exchange to remove antibodies from the blood. The treatment is most beneficial when started within 1-2 weeks of the appearance of symptoms.

Plasma exchange (plasmapheresis)

Antibodies are the proteins made by the immune system of the body that attack harmful foreign substances, such as bacteria and viruses. In Guillain-Barré syndrome, the immune system mistakenly makes antibodies against the healthy nerves of the nervous system.

In plasmapheresis, the blood taken from the body is separated into liquid part (plasma) and blood cells. The plasma which contains the antibodies is removed thus preventing the immune attack on the nerves. The blood cells are put back into the body, which stimulates the body to produce more plasma to make up for what was removed.

Immunoglobulin therapy

Immunoglobulins are proteins that the immune system of the body makes to attack infecting organisms or foreign substances.

In immunoglobulin therapy, immunoglobulins obtained from normal healthy donors are given to GBS patients intravenously. These immunoglobulins help by blocking the damaging antibodies that attack the nerves in Guillain-Barre syndrome.

Pain medications

Drugs like nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or acetaminophen are usually recommended for pain relief.

Supportive care and Rehabilitation

Supportive care is a very important aspect of treatment.

Respiratory support

Respiratory failure can occur in GBS, hence the patient’s breathing should be closely monitored. In case of respiratory distress, a mechanical ventilator may be used to help support or control breathing.

Monitoring of cardiac activity

Heartbeat and blood pressure should also be monitored regularly. The patient may be put on a heart monitor or equipment to track vital body functions.

Monitoring for infectious complications

The patient needs to be monitored regularly for signs of any infection such as pneumonia, urinary tract infections, or septicemia.

Nutritional care

It is important in the case of patients with severe dysphagia (difficulty in swallowing food). Care should be taken to prevent aspiration and subsequent pneumonia in high-risk patients. Patients on mechanical ventilation require enteral or parenteral feedings to meet the high-calorie requirement.

Prevention of thromboses

It is important to prevent complications like thrombosis that may arise as a result of prolonged immobility.

Low molecular-weight heparin (LMWH), other antithrombotic drugs, or blood thinners can be given to prevent lower-extremity deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and/or pulmonary embolism.

Inflatable cuffs may be placed around the legs. These devices fill with air and squeeze the legs thus increasing the blood flow through the legs’ veins and preventing clots formation.

Prevention of pressure sores and contractures

To prevent pressure sores and contractures from occurring, the caretaker should be instructed to manually move and position the patient’s limbs and also carry out frequent postural changes.

Bowel and bladder management

Although bowel and bladder dysfunction occurs for a brief period, it is important to manage these to prevent other complications including secondary infections.

Emotional support

In severe cases, patients may experience mental health problems including hallucinations, delusions, and sleep abnormalities. Psychological issues such as depression and anxiety may also occur. Appropriate counseling and medications are important in such cases.

Physiotherapy and rehabilitation

If muscle weakness persists after the acute phase of the disease, patients may require physiotherapy and rehabilitation services so as to restore muscle strength. Occupational and speech therapy may also be required in some cases.

Prognosis

GBS can be a devastating disease because it involves the sudden and rapid onset of weakness leading to even paralysis.

However, 70% of the patients recover fully.

Intensive care and proper adequate treatment of medical complications can enable patients of even respiratory failure to survive.

In most patients, the nerve damage worsens rapidly for about a few weeks and stops deteriorating by around 4 weeks.

Recovery may take a few weeks or a few years. The average recovery time is 6 to 12 months.

About 30% of patients have a residual weakness even after 3 years. About half of these experience long-term weakness and may require life-long use of a walker or wheelchair.

About 2-5% of patients may have a relapse of pain, muscle weakness, or tingling sensations many years after the initial episode.

Besides physical support and occupational rehabilitation, the patients usually also require psychological counseling and emotional support to cope up with sudden dependence on others for routine daily activities.

The mortality rate of the disease is about 3-13%. Causes of death in GBS include acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), cardiac arrest, sepsis, or thromboembolism.

References

- Ye Y, Zhu D, Wang K, Wu J, Feng J, Ma D, et al. Clinical and electrophysiological features of the 2007 Guillain-Barré syndrome epidemic in northeast China. Muscle Nerve. 2010 Sep. 42(3):311-4.

- Walgaard C, Lingsma HF, Ruts L, Drenthen J, van Koningsveld R, Garssen MJ, et al. Prediction of respiratory insufficiency in Guillain-Barré syndrome. Ann Neurol. 2010 Jun. 67(6):781-7.

- Mullings KR, Alleva JT, Hudgins TH. Rehabilitation of Guillain-Barré syndrome. Dis Mon. 2010 May. 56(5):288-92.

- Bersano A, Carpo M, Allaria S, Franciotta D, Citterio A, Nobile-Orazio E. Long term disability and social status change after Guillain-Barré syndrome. J Neurol. 2006 Feb. 253(2):214-8.

- Winer JB. Guillain Barré syndrome. Mol Pathol. 2001 Dec. 54(6):381-5.

- Hughes RA, Rees JH. Clinical and epidemiologic features of Guillain-Barré syndrome. J Infect Dis. 1997 Dec. 176 Suppl 2:S92-8.