Last Updated on January 27, 2022

Celiac disease or celiac disease is an autoimmune disorder that occurs due to ingestion of gluten and causes damage to the small intestine.

It is also called celiac sprue or gluten-sensitive enteropathy.

The disease occurs due to the inability to tolerate gliadin, the alcohol-soluble fraction of gluten.

When a patient suffering from celiac disease ingests gliadin, an immunologically mediated inflammatory response occurs in the body that damages the mucosa or the inner lining of the intestines. This results in indigestion and malabsorption of various nutrients present in the food.

Gluten is a protein found in wheat, barley, and rye.

In autoimmune diseases, the immune system of the body mistakenly identifies certain parts of one’s own body as foreign invaders. In response, it releases special antibodies, called autoantibodies that attack a person’s own cells and tissues. These autoantibodies can attack and damage the connective tissue and a variety of other organs (skin, joints, muscles, etc).

Celiac disease is one of the most common lifelong food-related disorders worldwide. The disease is estimated to affect 1 in 100 people throughout the world. It is most prevalent in Western Europe and the United States, with an increasing incidence in Africa and Asia. Females are affected slightly more than males.

The age distribution is bimodal, the first at 8-12 months and the second at 20-40 years. The disease may become apparent in infants when gluten ingestion begins. If untreated, symptoms might persist throughout childhood but usually diminish in adolescence. Symptoms often reappear in early adulthood.

Currently, the only effective treatment for celiac disease is a lifelong strict gluten-free diet. This can help manage symptoms and promote healing of the intestine.

Clinical features

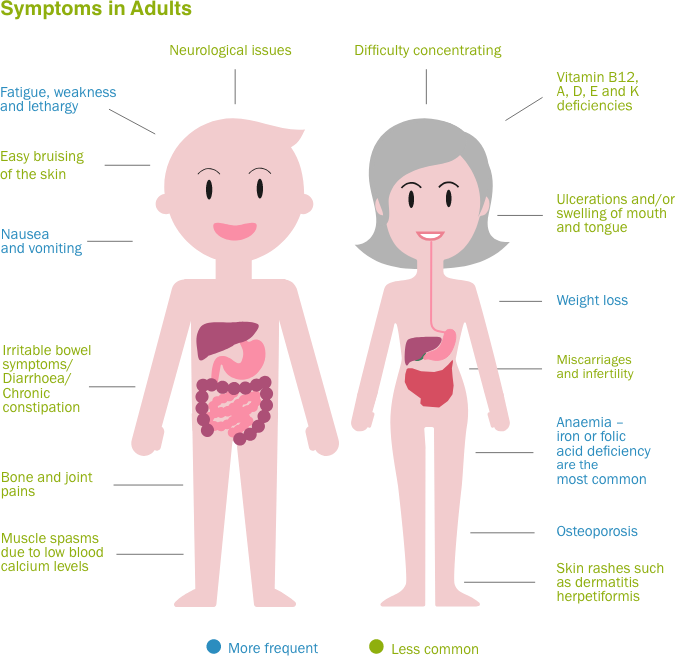

The signs and symptoms differ from person to person. The most common digestive symptoms include

- Diarrhea, which may be foul-smelling

- Stomach aches

- Bloating and flatulence

- Indigestion

- Nausea and vomiting

- Constipation

Many patients present with non-specific symptoms such as

- Fatigue

- Weight loss

- Anemia, mainly due to iron deficiency

- Mouth ulcers

- Headaches

- Osteoporosis (loss of bone density)

- Itchy rash (dermatitis herpetiformis)

- Infertility (difficulty in getting pregnant)

- Peripheral neuropathy (damage to nerves )

- Numbness and tingling in the feet and hands

- Ataxia (a condition affecting co-ordination, balance, and speech)

- Failure to thrive in infants

- Short stature

- Delayed puberty

- Damage to tooth enamel

- Irritability

- Neurological symptoms, such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), learning disabilities, etc.

Complications of celiac disease

If left untreated, the disease may result in:

- Malnutrition. This occurs due to the inability of the small intestine to absorb enough nutrients. It can result in anemia, weight loss along with slow growth and short stature in children.

- Weak bones. The inability of the body to absorb calcium and vitamin D can lead to weakness and softening of the bones (osteomalacia or rickets) or loss of bone density (osteoporosis) in adults.

- Lactose intolerance. Damage to the small intestine may result in lactose intolerance which causes abdominal pain and diarrhea after consuming dairy products that contain lactose.

- Cancer. Celiac disease patients who don’t consume a gluten-free diet are more prone to developing certain cancers such as intestinal lymphoma and small bowel cancer.

- Nervous system disorders. Patients with celiac disease can develop problems such as seizures, ataxia, or peripheral neuropathy (a disease of the nerves of the hands and feet resulting in pain and numbness).

- Infertility and miscarriage

Some people with celiac disease may have other autoimmune diseases such as thyroid disease, autoimmune liver disease, type 1 diabetes, lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, Sjogren’s syndrome, etc.

Causes of celiac disease

A combination of genetic factors and the consumption of foods containing gluten can lead to celiac disease.

Genetic factors play an important role as the disease is known to run in families. People having celiac disease have one of two groups of normal gene variants called DQ2 and DQ8. In the absence of these gene variants, it is very unlikely for a person to develop celiac disease. Around 30% of the world’s population has DQ2 or DQ8 gene variants. But only about 3% of people develop celiac disease. Thus although celiac disease usually does not occur in the absence of gene variants, their presence does not always imply that the person will develop the disease.

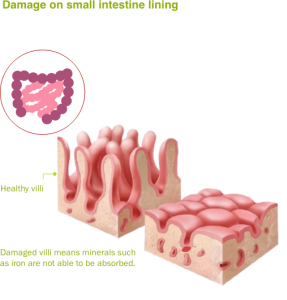

When genetically predisposed individuals consume gluten (a protein found in wheat, rye, and barley), their body mounts an exaggerated immune response against gluten. This overreaction by the immune system attacks the small intestine causing damage to the villi. (Villi are small fingerlike projections present on the inner surface of the small intestine that promotes nutrient absorption)

Once the villi get damaged, nutrients cannot be absorbed properly into the body. This leads to malnourishment in spite of adequate intake of healthy food.

Certain other factors may increase the risk of developing celiac disease. Certain gastrointestinal infections, changes in gut bacteria, and a greater incidence of infections in early life are thought to contribute to celiac disease. Besides these, any stress to the body such as surgery, pregnancy, viral infection, or emotional stress may lead to a flare-up of the disease.

Diagnosis

A detailed medical history and a thorough physical examination are the prerequisites for an accurate diagnosis.

Serological tests

These tests measure the level of antibodies against gluten in blood.

- Antiendomysium (EMA) antibodies

- Anti-tissue transglutaminase (tTGA) antibodies.

These antibodies are usually elevated in patients suffering from celiac disease. Serological tests should be performed while the person is still consuming gluten in the diet.

Stool examination

Due to malabsorption of fats, stools have a typical bulky, greasy appearance and rancid odor.

Endoscopy

A thin tube called an endoscope is inserted through the mouth and then gently passed down into the small intestine. A small camera attached to the endoscope allows the doctor to visualize the intestines and to check for damage to the villi.

Read more about Endoscopy: Procedure, Types, and Uses

Small intestine mucosal biopsy

An intestinal biopsy can also be performed during the endoscopy procedure. In this, a small tissue sample is removed from the intestine. This tissue is then examined by a pathologist under the microscope to look for specific changes of celiac disease.

Read more about Light microscope-Parts, Usage, Handling and Care

Read more about Types of Biopsies and their Applications

Genetic testing

Testing for human leukocyte antigens (HLA-DQ2 and HLA-DQ8) can be used to rule out celiac disease.

Once diagnosed with celiac disease, the following tests may also be carried out to assess the effect of the disease on the body.

- Complete blood counts: to detect anemia due to poor digestion.

- Serum iron and ferritin: to diagnose iron-deficiency anemia.

- Vitamin D, B 12, and folate levels: to look for vitamin deficiencies.

- C-reactive protein: to detect inflammation in the body.

- Kidney and liver function tests

- Skin biopsy: In case of suspicion of dermatitis herpetiformis (an itchy rash caused by gluten intolerance), a skin biopsy may be required to confirm it. Performed under local anesthesia, it involves a tiny skin sample being taken from the affected area which is then examined under a microscope.

- DEXA scan: It is a type of X-ray that measures bone density. It helps to diagnose osteoporosis that occurs due to loss of mineral bone density (as a result of poor absorption of nutrients) resulting in weak and brittle bones.

Treatment

Gluten-free diet

The only effective treatment of celiac disease is to permanently remove gluten from the diet.

This allows the intestinal villi to heal and to begin absorbing nutrients properly. The symptoms start improving within days of removing gluten from the diet. However, one shouldn’t stop eating gluten until a diagnosis is made. Removal of gluten from the diet prematurely may lead to inaccurate test results.

A doctor or dietitian may be consulted who can teach the patient about how to avoid gluten while following a healthy and nutritious diet. It is also important to learn how to read food product labels so as to identify any ingredients that contain gluten.

Vitamin and mineral supplements

In case of nutrient deficiency, the patient may be prescribed vitamin and mineral supplements containing iron, vitamin B 12, folic acid, vitamin D, copper-zinc, etc.

Medicines to control intestinal inflammation

In case of severe damage to the intestines, steroids may be prescribed to control inflammation. Besides steroids, other drugs like azathioprine may also be used to treat inflammation.

Treatment of dermatitis herpetiformis

Dermatitis herpetiformis is treated with a gluten-free diet and an oral antibiotic called dapsone. Dapsone helps to relieve itching usually within an hour. If dapsone doesn’t help, other medicines like sulfapyridine or sulfasalazine may be prescribed.

Nonresponsive celiac disease

Some people with celiac disease don’t respond to what they consider a gluten-free diet. This usually occurs due to the persistence of gluten in their diet; often from not-so-obvious sources. Strict adherence to avoid all forms of gluten is required in such cases.

Other causes of non-responsive celiac disease might be the presence of the following conditions:

- Bacterial overgrowth in the small intestine

- Microscopic colitis

- Pancreatic insufficiency

- Irritable bowel syndrome

- Difficulty digesting sugar found in dairy products (lactose), honey and fruits (fructose), or sugar (sucrose)

Refractory celiac disease

In some patients, the intestinal injury of celiac disease doesn’t respond to a strict gluten-free diet (taken for 6 months to 1 year). Inadvertent exposure to gluten is the main cause of persistent intestinal injury and must be ruled out before making a diagnosis of refractory disease.

Such cases may require treatment with steroids or immunosuppressants (such as azathioprine). In some cases, alternative causes of intestinal damage may have to be searched for.

Prognosis

In patients who are correctly diagnosed and treated adequately, the prognosis is excellent. Patients who do not respond to gluten withdrawal and corticosteroid treatment usually have a poor prognosis.

References

- Martucciello S, Paolella G, Esposito C, Lepretti M, Caputo I. Anti-type 2 transglutaminase antibodies as modulators of type 2 transglutaminase functions: a possible pathological role in celiac disease. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2018 Nov. 75(22):4107-24.

- Green PH, Lebwohl B, Greywoode R. Celiac disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015 May. 135(5):1099-106; quiz 1107.

- [Guideline] Rubio-Tapia A, Hill ID, Kelly CP, Calderwood AH, Murray JA, American College of Gastroenterology. ACG clinical guidelines: diagnosis and management of celiac disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013 May. 108(5):656-76; quiz 677.

- Kagnoff MF. Celiac disease: pathogenesis of a model immunogenetic disease. J Clin Invest. 2007 Jan. 117(1):41-9.

- Green PH, Cellier C. Celiac disease. N Engl J Med. 2007 Oct 25. 357(17):1731-43.